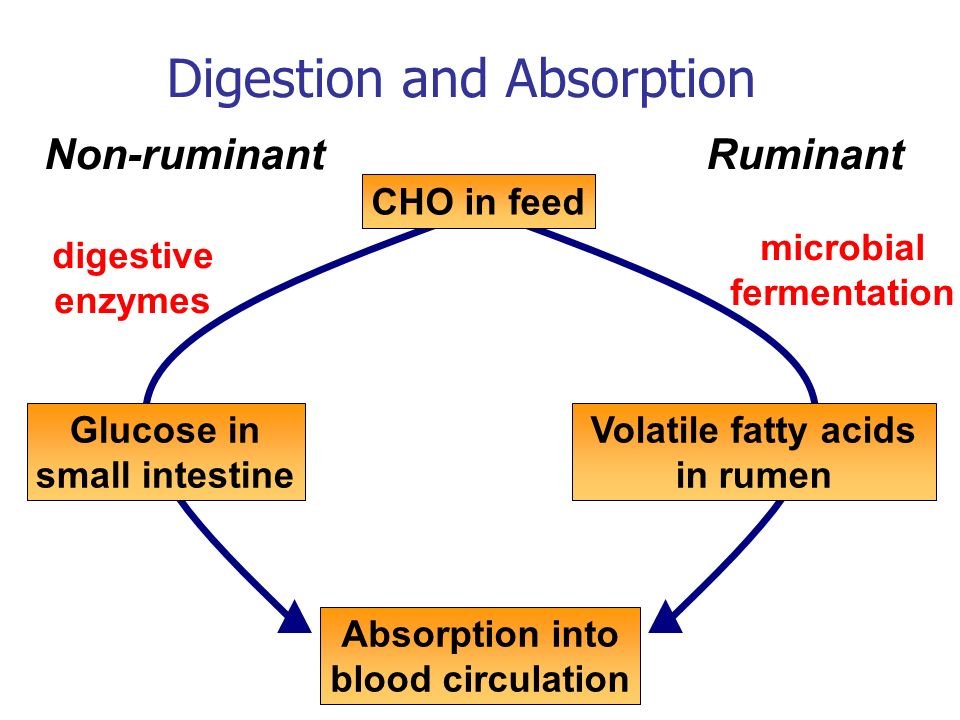

Animals are classified as ruminants and non-ruminants based on their digestive systems and how they process food, particularly carbohydrates.

Table of Contents

The Tale of Two Digestions: How Ruminants and Non-Ruminants Break Down Carbs

Below is the tale of two digestions how Ruminants and Non-Ruminants break down carbs. The breakdown process of Ruminants and Non-Ruminants are different.

Carbohydrates are a vital source of energy for all animals, but the way Ruminants and Non-ruminants animals digest them differs significantly. This difference is due to the unique digestive systems each group possesses. Here, we delve into the fascinating world of carbohydrate digestion in ruminants and non-ruminants.

Ruminant Digestion: A Fermentation Frenzy

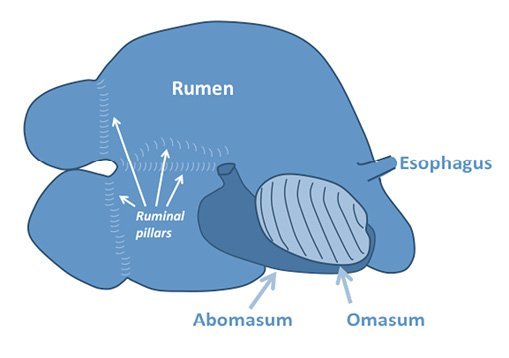

Ruminants, such as cows, sheep, goats, and deer, have a complex four-chambered stomach specifically adapted to break down tough plant material, including carbohydrates like cellulose. Their digestive system involves a fascinating process called ruminal fermentation.

The Players:

- Rumen: The largest chamber, where microbial fermentation takes place.

- Reticulum: Often referred to as the “honeycomb” due to its net-like structure, it sorts and returns large food particles back to the rumen for further breakdown.

- Omasum: Absorbs water, electrolytes, and fatty acids.

- Abomasum: The “true stomach” where acid digestion occurs, similar to non-ruminants stomachs.

The Fermentation Process:

- Ingestion and Rumination: Ruminants first ingest their food quickly and then regurgitate it as cud for further chewing and breakdown. This allows for better mechanical breakdown of plant material.

- Microbial Feast: The rumen is a haven for a diverse population of microorganisms, including bacteria, protozoa, and fungi. These microbes break down complex carbohydrates like cellulose and hemicellulose, which non-ruminant animals cannot digest on their own.

- Fermentation Products: Through this microbial fermentation process, various products are generated, including:

- Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs): These short-chain fatty acids, primarily acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid, are the primary energy source for ruminants. They are absorbed directly through the rumen wall into the bloodstream.

- Microbial Protein: The microbes themselves serve as a valuable source of protein for ruminants.

- Digestion Continues: After sufficient fermentation, the partially digested food moves to the reticulum and omasum for further processing and absorption of water and electrolytes.

- Abomasal Action: Finally, the food reaches the abomasum, where stomach acid and digestive enzymes break down remaining proteins and carbohydrates for absorption in the small intestine.

Benefits of Ruminant Digestion:

This complex fermentation process allows ruminants to:

- Extract energy from complex plant material unavailable to other animals.

- Synthesize essential amino acids and B vitamins with the help of rumen microbes.

- Have a more efficient digestive system, extracting maximum nutrients from their food.

Non-Ruminant Digestion: A Straightforward Approach

Non-ruminant animals, such as humans, dogs, cats, and pigs, have a simpler digestive system compared to ruminants. They lack the rumen and its microbial community, relying primarily on their own digestive enzymes to break down carbohydrates.

The Digestive Journey:

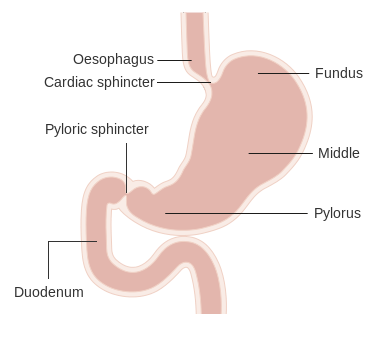

- Ingestion: Food is taken in through the mouth and mechanically broken down by chewing.

- Salivary Enzymes: Saliva contains enzymes like amylase that begin the breakdown of carbohydrates, particularly starches, into simpler sugars.

- Esophageal Passage: The food then travels down the esophagus to the stomach.

- Stomach Acid and Enzymes: In the stomach, strong stomach acids and enzymes further break down carbohydrates and proteins.

- Small Intestine Absorption: The partially digested food mixture then enters the small intestine, where pancreatic enzymes and enzymes lining the intestinal wall complete the breakdown of carbohydrates into simple sugars like glucose. These sugars are then absorbed into the bloodstream through the intestinal villi.

- Large Intestine and Elimination: Undigested material and fiber move to the large intestine, where water is absorbed and remaining waste is eliminated.

Limitations of Non-Ruminant Digestion:

While non-ruminant digestion is efficient, it has limitations:

- Limited Cellulose Digestion: Non-ruminants cannot break down complex carbohydrates like cellulose, leading to the loss of this potential energy source.

- No Microbial Protein Synthesis: Non-ruminants lack the benefit of microbial protein production in the digestive tract.

Conclusion

Ruminants and Non-ruminants : The digestive systems of ruminants and non-ruminants are fascinating adaptations that allow them to thrive on different diets. Ruminants, with their complex microbial fermentation, can extract energy from tough plant material, while non-ruminants rely on their own digestive enzymes for a more streamlined process. Understanding these differences allows us to appreciate the remarkable diversity of life and the unique strategies animals have evolved to obtain the nutrients they need.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What kind of carbohydrates are digested in ruminants and not man?

One kind of carbohydrate that ruminants can digest but humans cannot is cellulose. Between the small and big intestines of ruminants is a huge sac-like structure where certain microorganisms break down cellulose-containing meals.

What is the product of carbohydrate digestion in ruminants?

In the small intestine, dietary carbohydrates are broken down into glucose, fructose, and/or galactose and then absorbed into the blood. Numerous factors can affect how well carbohydrates in food are absorbed and digested.

What enzyme breaks down carbohydrates?

Amylase (made in the mouth and pancreas; breaks down complex carbohydrates)

Related Articles